David Smith gets up close with Beefeater Master Distiller Desmond Payne to find out more about his quest to create the perfect sipping gin. And he ends up pretty impressed.

David Smith gets up close with Beefeater Master Distiller Desmond Payne to find out more about his quest to create the perfect sipping gin. And he ends up pretty impressed.

There are many popular spirits whose characters are derived from the interplay between the flavours of the spirit and wood: whisk(e)y, rum, brandy, and tequila. Even some liqueurs, such as Benedictine, are matured, but what about gin?

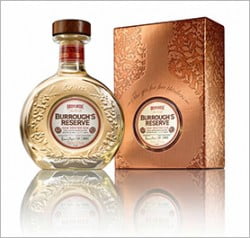

In his desire to create an ultra-premium gin that could be enjoyed neat as an alternative to a whisky or brandy at the end of the meal, Beefeater’s Master Distiller, Desmond Payne, investigated the growing niche market for matured gin. The result of his quest to make a gin for free thinkers was Burrough’s Reserve.

The History of Matured or Aged Gin

Matured gin, also known as aged, rested or yellow gin, has its origins many centuries ago when gin was commonly stored, shipped and served from wooden barrels. Barrels were used to transport and store a wide range of products, including beer, wine, vinegar, water, oil, nails, and gun powder. They came in two categories: eet or fluid, which held liquids; and Dry for dry goods.

In the 18th century, barrels were filled with gin at the distillery, before being directly shipped to the Public Houses and Inns, so it is unlikely that much attention would have been paid to the barrels’ previous contents, as long as they are water-tight; any effect on the gin was incidental. It is also worth noting that the barrels would not have been fired or charred to help with flavour extraction as they are today.

Modern whisky producers tend to stop using barrels after their fourth use, as most of the impact that the wood has on the spirit is gone. It is therefore easy to imagine that barrels that had been used dozens of times would have had a very small impact on the gin placed in them.

In 1861, the Single Bottle Act was passed, which allowed gin to be sold by the bottle. This later enabled the increasing number of gin house and brands, such as Beefeater in 1876, to have closer control over their product once it had left their distillery, helping to build up the recognition for quality that they have today.

In the early 20th century, two brands released gins that had been deliberately matured: Booth’s of London and, in 1929, the American-Canadian Seagram’s ‘Ancient’. Booth’s discontinued theirs in the 1970s, whilst Seagram’s continued production until 2010. The effect of wood on these gins was quite light and these “yellow” gins were marketed for their mixability, thanks to their mellow and smooth character. They found favour with famous drinkers David Embury and Kingsley Amis.

Burrough’s Reserve

Fast-forward to the present day, and Burrough’s Reserve is made using a scaled-down version of the original, eight botanical Beefeater London recipe, on an original, 268-litre still that came from the first Chelsea distillery of Beefeater founder, James Burrough. In contrast, the normal stills used for Beefeater are around 25 times the size. Distilling is not a linear process and so distilling on the smaller still creates a gin that is very similar, but not identical to Beefeater, with its own nuance and character.

What makes gin stand out from most other spirits is that its flavour mostly comes from its botanicals and so it has plenty of character even before maturation. As a result, achieving balance once you have added all of the rich and complex flavours that maturation in wood can add is a bit tricky.

Desmond was aware of this and, having tried some of the early aged gins, was not sure if it could be done. However, his opinion changed after he tried a barrel-aged Negroni from a bar in Oregon, US; at that moment, he could see both that it could be done and that it was worth doing.

Which barrel?

Most matured spirits are aged in ex-bourbon, American oak casks due to their availability and attractive price (US law dictates that Bourbon must be aged in new (virgin) barrels that cannot be reused). But there is no real connection between gin and bourbon, and the nature of this ultra-premium Beefeater gin called for being creative so an alternative had to be found.

The solution came from Bordeaux, France, the home of Lillet, a wine aperitif manufacturer who, like Beefeater, are owned by Pernod Ricard. Many readers may be familiar with Lillet Blanc, but Lillet also make their own reserve wine from time-to-time: Jean de Lillet is a mix of 80% Semillon, 15% Sauvignon Blanc, and 5% Muscadelle. The wine is aged in 225 litre wooden barrels for 12 months and its ingredients include kina (quinine as used in tonic water) and sweet orange from Seville (which is also a Beefeater botanical).

James Burrough’s Reserve is aged in ex-Jean de Lillet casks for a period of around 4 weeks for the first fill and 5 weeks for the second fill. For each bottling run of 1,800 bottles, around three casks – both first and second fill – are blended together and then bottled at 43.0% ABV.

What about the taste?

The Beefeater boffins have created a flavour wheel to demonstrate how the flavour of the spirit changes at different temperatures.

At Room Temperature

Nose: Bright juniper with hints of woody spice and notes of sweet orange and crème brulee.

Taste: Complex, with an interplay between creamy vanilla and butterscotch notes and those of fruity spice and citrus; all of this is wrapped up with a kick of juniper towards the end. Tasting Burrough’s Reserve alongside the Jean de Lillet, with its rich flavours of fruit, cinnamon and nutmeg, the impression that the barrels make on the gin is evident.

From the fridge (around 5˚C), Burrough’s Reserve has more floral notes on the nose and the texture is more viscous. Distinctive flavours of orange blossom and orange peel come through, accompanied by some butterscotch.

From the freezer (around -5˚C), the nose is softened, with notes of citrus and some spice, whilst the texture is thick, indulgent and smooth, adding depth to the drink. The flavour is a mix of juniper and light, confectionery spice, and is followed by a long and lingering, dry finish.

In Conclusion

A few years back, the idea of drinking gin neat was pretty much unheard of outside naval circles, but today it is gradually becoming more popular, helped by distillers producing matured gin and creating more innovative character profiles. Beefeater 24 was the first gin that I preferred to drink neat and so it seems fitting that Beefeater produce Burrough’s Reserve – a gin that is perfect for sipping.